Here is a very interesting and detailed story about one of Canada’s greatest athlete’s and hero’s… Marilyn Bell! As an open water swimmer, marathon swimmer and or Canadian… it’s a good story to know! Still makes us proud after 60 years!

Cheers,

Rob

by MIKE TOWNSHEND on Jan 29, 2014 • 6:30 am

In the morning, usually at about 6 a.m., Marilyn Di Lascio hits the pool at Woodland Pond in New Paltz with her friends. The room’s high wooden ceilings look a bit like a church — a metaphor the 76-year-old swimmer enjoys.

The room is her chapel, she says. Even after her brief but epoch-making professional swimming career, and despite a degenerative back condition, water still holds magic for her. It’s still a lot like her first love.

If you don’t know her story — as many Americans outside of hardcore swimmers do not — Marilyn Bell Di Lascio comes across as a nice old lady — charming, polite and quick with a joke. She’s down-to-earth, humble to the point of self-deprecation at times.

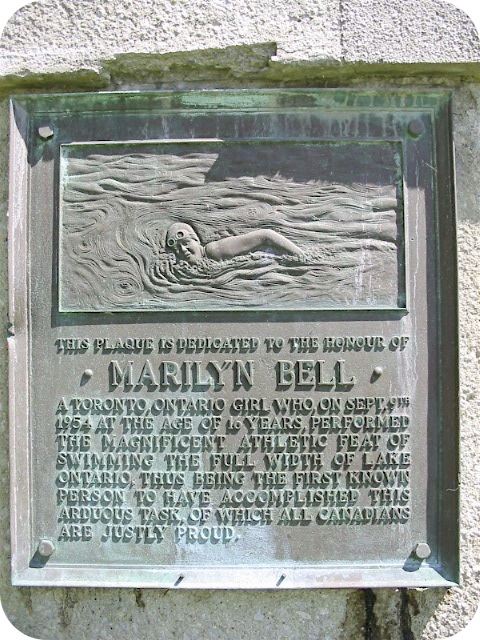

Talking to her, it’s a bit hard to believe she’s an international swimming legend — the first person ever to succeed at swimming across Lake Ontario.

But at age 16, back in 1954, up against a famous American shoo-in, she conquered the big lake when no one said it could be done — much less by a woman. In doing so, she became a Canadian national sports hero.

Early days: Learning to swim

Originally from Toronto, Marilyn Bell started swimming late in life compared to some. “I didn’t learn to swim until I was about 9 years old,” she said. “I took swimming lessons for the first time that summer. I took to it. I loved it. I can still remember the first time I floated by myself. I can remember that sensation of popping up in the water.”

Originally from Toronto, Marilyn Bell started swimming late in life compared to some. “I didn’t learn to swim until I was about 9 years old,” she said. “I took swimming lessons for the first time that summer. I took to it. I loved it. I can still remember the first time I floated by myself. I can remember that sensation of popping up in the water.”

By the end of the summer, her swim coach invited her to join a competitive swim club. At first she didn’t have rhythmic breathing in her skill set. The first race she won, she didn’t breathe in the water at all — which left the official timing her swim a little baffled.

“I remember saying, ‘I haven’t learned how’,” she said. “So that was like, ‘okay if you can hold your breath a long time, that helps’.”

She swam her first mile in a pool by age 10. “Nobody thought I could do it. Not even my teacher. But he said, ‘Well try. Go for as long as you can and see what happens.’ And I did.”

Far from being a champion early on, the young Marilyn Bell was an underdog.

“I would usually place fourth of fifth. On a really super good day, when one of the top swimmers didn’t show up, maybe I would place third and get a medal,” she remembered. “I usually did well on a relay — not because I was so great, but because the other girls were so fast.”

Early on, she had endurance, but the speed didn’t come. “I could never get there based on my own ability — no matter how hard I tried. I tried so hard. My parents sent me to different instructors to try to refine my stroke. I just couldn’t go as fast as I wished I could.”

One of those new swim instructors happened to be Gus Ryder — who became one of Canada’s most famous coaches. Both he and Marilyn were eventually inducted into the Canadian Sports Hall of Fame. She’s also an International Swimming Hall of Famer.

He saw something in her that others didn’t. Where others saw obstinacy, he saw determination. “It was during that period of time that he knew I was working so hard. I would be the first one into the pool, the last one to get out.

“He said, ‘You never complained. You just did everything I told you to do. There was just one thing missing: You weren’t hungry enough. You were more concerned about your team members doing well. So you didn’t concentrate’.”

Something about the way she swam gave him an idea. He started grooming her to become a long-distance open water swimmer. At age 13, financial difficulties at home almost ended her sports career before it started.

“My parents didn’t have a lot of money,” she said. “I don’t even think you would call us a middle-class family. So money was very scarce, and my parents decided that since I wasn’t excelling — and it was costing money for me to swim — that they were going to pull me out of the program. That for me was like a catastrophe. I couldn’t imagine a life without swimming.”

The team was a huge part of her social life back then. Also, she taught at Ryder’s now-famous Lakeshore Swim Club, teaching swim lessons to the physically disabled.

“I was actually working with handicapped children. That was the era of the polio sweep in the country. And we had a lot of young people — some younger than me, many older than me — who had come down with polio and had been left paralyzed,” she said. “He was one of the first people in the swimming world to say, ‘Hey, we can make a difference here’.”

Ryder worked out a special deal with her parents. Marilyn worked in the office at the swim club’s pool in exchange for continued lessons. “It was really a live-saving gesture to me.”

She started training in hopes of making the 1952 Olympic Games in Finland. She tried out, but the Olympics weren’t in the cards for her. At age 14, she’d turned professional. She swam in a 3-mile, professional women’s race on Lake Ontario. Those early pro races retreaded her old pattern — placing third or fourth — but she was still pleased.

“The first year, I placed fourth. I was thrilled because I’d won $300, which for a kid who had no money was really a lot of money.”

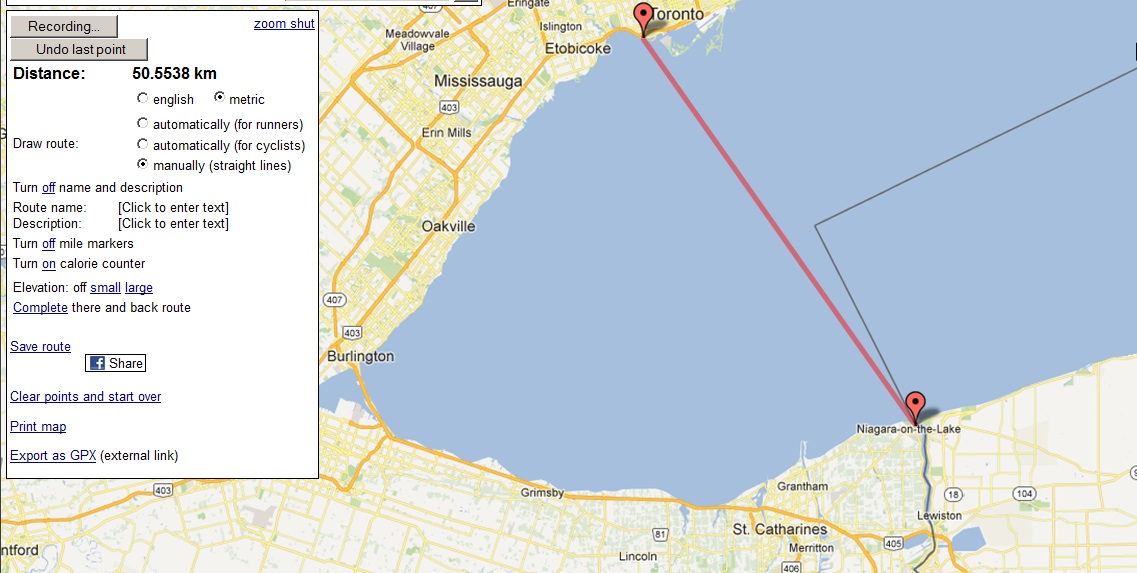

A challenge went out for a marathon swimmer to cross Lake Ontario — from Youngstown, NY to the shore in Toronto. American swimmer Florence Chadwick had been offered a $10,000 prize from the Canadian National Exhibition (CNE) to cross the lake. Chadwick was the favorite, because she was the first woman to swim the English Channel in 1950.

Secretly, Gus Ryder started grooming Marilyn Bell to make that swim. But first she needed to prove herself. The Youngstown-to-Toronto route is 32 miles.

“The furthest I think I’d ever swum was 7, 8 miles tops,” she said. Her coach made her train by swimming for 10 hours straight, to prove she could do it. She did.

He signed her up for a 26-mile race around Absecon Island in Atlantic City, NJ. That one race had a huge impact on Marilyn’s personal life. Maybe as much as the Lake Ontario swim, it changed her life.

“The best part about that was that was where I met my future husband. He was a lifeguard on the beach where we were training,” she said.

In Atlantic City, there were 39 swimmers — of which only seven survived the brutal marathon around the island. Marilyn placed seventh overall, but she was the only woman across the finish line. “That was pretty exciting.”

The big lake

For Canadians, that CNE didn’t sponsor a native swimming champion, but instead the American Florence Chadwick created a lot of controversy. As a long shot competitor, considered too young to pose a serious threat, Bell stayed away from the heat.

“I was not one to be a part of controversy. And it was a very controversial issue, of course. And there were other Canadian women that could have easily challenged her,” she explained.

Winnie Roach Leuszler — a famous Canadian swimmer and a mentor and hero to Bell — also threw her hat in and challenged Chadwick. The three women would all set off from Youngstown on Sept. 8, 1954.

Bell Di Lascio still credits a lot of her success to circumstance. “When I think back, it was just I think being in the right place at the right time and having a coach who was patient — and who knew how I ticked.”

Unusual for an open water marathon swim today, the whole event was done with subterfuge.

“It was cloaked in secrecy, first of all, because the Canadian National Exhibition — which was the sponsoring organization — had made this bona fide contract with Florence Chadwick,” she said. “She came into this controversial situation. There were two newspapers, the Toronto Star and The Toronto Telegram. They were always at war with each one another.”

Bell’s coach pitched the papers her story to gain sponsorship and publicity on the race — without her knowledge. But they also needed transportation, which the media — hungry for pictures of the action — promised to provide.

“It turned out the Toronto Star took the bait,” she said. “My coach pitched it to

them. He knew that he needed backing for his swimmer — one way or another. The Telegram turned it down, and the Star said yes. So they provided a boat and a horde of newspapers, reporters and photographers.”

Canadian journalism students still study the race — mostly because of how it reflects on the media. The 1950s were such a cut-throat, blatantly competitive period in Toronto that reporters sabotaged their competition’s cars during the swim.

Recovering in the ambulance after the swim, Bell later learned the woman she thought was a nurse was a Telegram reporter. Her private conversation with her friend, during the ambulance ride, ended up on the front page verbatim.

At Youngstown, at the mouth of the Niagara River, Bell prepared to get into the water. The weather looked iffy on Sept. 6 — the original night of the swim.

“We had high winds and cold water, and I guess a cold front moving through on the lake. And Lake Ontario is no place you want to be in bad weather,” she said. “Florence had put in her contract that she would decide when to go.”

They delayed two days. On Sept. 8, the weather was still bad, but it was breaking. Chadwick entered the water at the Coast Guard station at about 11 p.m., but the news the race had started wasn’t immediately transferred to Bell or Roach.

“We had maybe an hour to prepare. Unfortunately, my dad and my coach went for a walk,” she explained. “We were all living on this little boat. It was very tense — really close quarters. It was a beautiful yacht, but it wasn’t designed to have hordes of people.”

After a mad dash to get her dad and coach to the yacht, they took a risk to get the 16-year-old swimmer on the lake sooner. They hitched a ride with a stranger, took her by car to the Coast Guard station, telling her to dive in the river, swim out into the lake — until the escort boat could meet her.

“It was 11 o’clock at night. No moon. I mean, it was a stormy night. And there were all kind of floodlights at the Coast Guard station. So Florence came down. She dove in. She took off,” Bell Di Lascio said. “So I was standing there looking out at the dark. I’d never swum at night before. I was petrified of night swimming.”

Her coach convinced her that the dark wouldn’t matter once she got swimming.

“The last thing he said to me before they transported me to the start was, ‘When you dive in, just swim out of the river … Just swim straight out and we’ll find you. I’ll find you.’ Which, in retrospect, was like this crazy, crazy thing. Why, number one, was he so sure that he would find me? And why did I believe him?

“The last thing he said to me before they transported me to the start was, ‘When you dive in, just swim out of the river … Just swim straight out and we’ll find you. I’ll find you.’ Which, in retrospect, was like this crazy, crazy thing. Why, number one, was he so sure that he would find me? And why did I believe him?

“It was the coach and the swimmer. I had so much faith and trust in him.”

With Chadwick, the favorite, gone, those big floodlights turned off. Surrounded by black on all sides, she remembers crying as she swam — unsure if she’d find her coach or her escort crew.

“I couldn’t tell where the water ended and the sky started,” she said. “It seemed endless.”

After a while, she saw dim lights in the distance. She kept going. “Finally, I heard Gus’s voice. He was calling me. ‘Marilyn. Marilyn.’ He had a big powered flashlight. So I swam to the light and we were on our way.”

Winnie Roach had to give up because she never found her escort boat. “She swam for several hours and finally a fishing boat picked her up and brought her back to shore.”

Marathon swimming doesn’t necessarily lend itself to knowing what the competition is up to. Bell remembers not really being aware of Roach’s fate or really what Chadwick was doing.

“My goal as I started was I just wanted to swim further than Florence Chadwick did, because I didn’t believe she could do it. I never told anybody that. Years later I told my coach after I stopped swimming,” she said. “I wanted to prove that a Canadian could swim farther than the American. For me, that’s what it was about.”

She swam through the night. The lights shining on her swim attracted disgusting lamprey eels — a leech-like bloodsucking invasive species that plagues the Great Lakes.

“At night, you have no warning. They’re just wrapping around your leg. But I hit them,” she said. “We were trained to try to hit them in the head with your fist — and then they lose that suction.”

Toronto, off in the distance, never seemed to get any closer. She swam through the whole next day, her coach Gus Ryder passing food to her from the boat. She even fell asleep a few times, getting jostled back to consciousness by her coach yelling at her or the crew banging on the boat.

To keep her motivated, her friend Joan Cooke — another swimmer — skipped work and took a water taxi out to meet the escort boat. Near the end, she jumped in the water to keep Bell motivated and swam next to her.

It was about 8 p.m. the following evening, Sept. 9, 1954, when she made it to the shore in Toronto — nearly 21 hours later. Bell was in a daze.

“By the time I finished, I didn’t actually know I was finished. I didn’t know I had completed the swim. I actually fought people who were trying to touch me and pull me out. I kept fighting and swimming away,” she said. “I don’t remember touching the break wall.”

People on the water had gathered in boats, which confused Bell, who was addled by exhaustion. She remembered thinking she dreamed about ghostly figures floating on the water at the end of the race.

People on the water had gathered in boats, which confused Bell, who was addled by exhaustion. She remembered thinking she dreamed about ghostly figures floating on the water at the end of the race.

“I remember seeing faces. They were like dismembered bodies; heads and shoulders. I didn’t see the full bodies, because it was dark.” Only later did she figure out they were real people on boats.

Everywhere on shore, a huge cheer erupted. Throughout the day — as it became clear Bell was the only one left in the water — bitter rivalries ended and people rallied around the one swimmer with a chance. The radio and papers covered her every move. People knew she was struggling in the swim’s final hour. When she got to land, everyone knew her name.

“They’d been broadcasting all day long,” she said. “Nobody expected me to be the one left, but they were so invested in what I was trying to do it that suddenly it was like they were all on the same team.”

After the race

Fame was immediate for Marilyn Bell, who became an emblem of national pride in Canada during an era where it seemed like the U.S. always won. “I was like I was everyone’s kid,” she explained.

After the win, she toured schools giving motivational speeches to kids and ran the publicity circuit. She flew around Canada and the States appearing on TV shows or radio. She got a ticker-tape parade. During that time, she appeared as a guest on “The Ed Sullivan Show.”

“Compared to the aftermath, the swim was easy,” she explained.

Bell had been attending a small Catholic convent school before she made the swim. Touring to talk about her accomplishment — and avoiding the glare of the press — meant that life would never be the same.

“It was hard on me,” she said. “For several weeks after the swim, I couldn’t go back to school. I was devastated.”

Her family also lived in a hotel after she became the first person to swim Lake Ontario, since reporters had her childhood home totally staked out.

Despite their contract with Florence Chadwick, who didn’t finish, CNE awarded the $10,000 prize money to Bell. She continued to swim, but now everyone in Canada and abroad had their eyes trained on her performances.

At age 17 she swam the English Channel. And at age 18, she attempted to swim the Strait of Juan de Fuca — between the Washington State and Victoria, British Columbia. Her first attempt in 1956 ended in failure.

“There was no expectation that I was going to fail,” she remembered. “When I tried it, no woman had successfully done it.”

During her first attempt, there was perfect weather. Still she only made it three-fourths of the way. “The water didn’t beat me. I beat myself,” she said.

On Aug. 26, 1956, during bad weather, she made another attempt — at first intending it as a practice swim. After 10 hours and 38 minutes, she made it to the other side.

“That was, for me, my crowning achievement,” she said. “I went back and did it, because I had to try.”

After Juan de Fuca, she officially retired from professional swimming. She’d stayed in touch with that lifeguard from Atlantic City, one Joe Di Lascio and they were in love. They knew they were going to get married soon.

She didn’t look back. She didn’t rethink her decision. “I was in love. I wanted to get married. I wanted to have a family.”

Her husband’s family lived in New Jersey and she decided to move to the States. Her wedding day also was an event in Canada. The media covered it from afar, but it was a small, intimate ceremony with about 60 people.

“The day we were married was the day I left Canada,” she said.

A public legacy, a private life

In America, Bell Di Lascio became a teacher, in part, because of the influence of her coach Gus Ryder. Before retiring, she taught for 20 years, teaching preschool, second and third grades — along with some special education classes.

Back in Toronto, and Canada in general, they continue to celebrate Marilyn Bell as a hero. The park where she landed was renamed the Marilyn Bell Park. She’s had two books written about her, two movies made about her life — one a documentary, another a TV mini-series — countless accolades and a ferry boat named in her honor.

Although living in the U.S. has meant some anonymity, fans still find her whenever a new edition of a Canadian textbook mentions her name — or when someone writes about her old feats in a sports journal. After the 1990s, Internet articles also kept her name fresh in people’s minds.

“It’s amazing how people would find me,” she said. “It’s never dried up.”

Bell Di Lascio added: “I still get, surprisingly, a lot of contacts from school kids.”

Later this year, on Sept. 8-9, it will be the 60th anniversary of her famous Lake Ontario crossing. In the past, anniversaries of the swim have led to huge celebrations. Di Lascio didn’t know if Toronto has something cooked up for 2014, however.

What she accomplished on the lake still has reverberations. According to The Globe and Mail, only 56 other swimmers have crossed the lake since Marilyn’s first success. Most of them have been women, including the youngest of them — a 14-year-old girl in 2012.

It didn’t really occur to her back then, but Marilyn Bell Di Lascio also sparked and pushed forward the feminist movement in her country.

“It was an awakening, and parents picked up on that. The media picked up on that too,” she said. “The most interesting thing is that I didn’t pick up on that until years later.

“My husband had always said to me when the feminist movement was really getting going, he said, ‘I know you don’t believe this. I know you don’t see yourself in that picture, but you were a catalyst’.”

She and her late husband ended up having four kids. Di Lascio lives in New Paltz now at the retirement community Woodland Pond to be closer to her kids and grandkids, who live in the area.

At the retirement home, people were surprised to learn who Bell Di Lascio was, but they’re taking it in stride. Whenever Woodland Pond gets a Canadian visitor, they’re usually pretty excited to learn that Bell is in the house.

Bell recently gave a talk entitled “Evening with a Champion” to other seniors about her swimming career.

Even after years of motivational speaking, teaching and touring the world, she still has some more wisdom to impart.

“It’s so important when we fail at something that we don’t give up on ourselves. Perhaps we’re trying to do something we don’t have the skills for, or the timing isn’t right,” she said. “But that doesn’t mean you don’t keep trying. You may have to reset your direction or change your goal.

“It’s so important, especially for young people, to know that it’s okay to fail. The worst thing to do is to be so afraid of failing that you don’t give it your best shot.”